If you are of the internet age, of those who know more about dye transfer as a mystic process from a distant age. As a process steeped in, and dripping with the badge of chemical craft — meticulous step by step make no error darkroom work, then you probably know few names of its thousands of practitioners.

You know those who have been proclaimed by the forums as keepers of the skill. They aren’t the folks I knew. Of course I knew of Eliot Porter, but then I also knew of his assistants as well as some of the printers who worked at the labs who printed for him.

The photographer most people know is William Eggleston. A man of many printers.

The person most of you from the pop-photo, camera store, workshop trained photographers have heard of is Ctein. He isn’t the person I think of as the main dye guy. To me, he is a tech writer who was given work by Frank McLaughlin of Kodak.

I have mixed feelings about this post. Ctein can’t do any harm — neither can he do any good — not for you, not if you are trying to learn about making prints. The information of doing that exists in better, more usable form in several books and places. The process as it is done in this century is fading again. The last orthomatrix film coating was in 2018. That was done by a coater that no longer has the equipment used for that type coating.

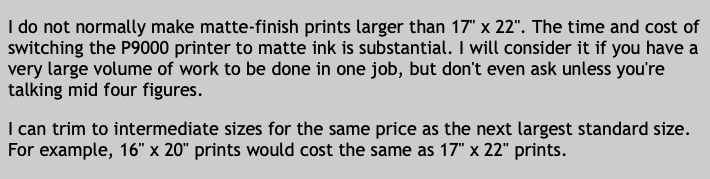

What bothers me is the sense of privilege along with the power given to someone who spent so much time staking claim to a skill so widely held — an ability to make prints many times more often, to even higher demands with a seemingly endless array of problems. A commercial lab doesn’t often reject possible clients. Our success was based upon solving a clients problem, not by setting out the reason we wouldn’t take their job. “we’d have to change a printer”

limitations … perhaps after years doing dyes didn’t provide enough profit to afford two printers in his second stage..

he doesn’t have to tell his story; others will repeat it. By association they gain favor.

“I know great people, must mean I’m a great person.”

So, what’s my problem. None. I understand all of this — I even understand that you will not change your viewpoint. You shouldn’t.

Too bad you never met the real dye guys. Too bad you never became one.

You must be logged in to post a comment.